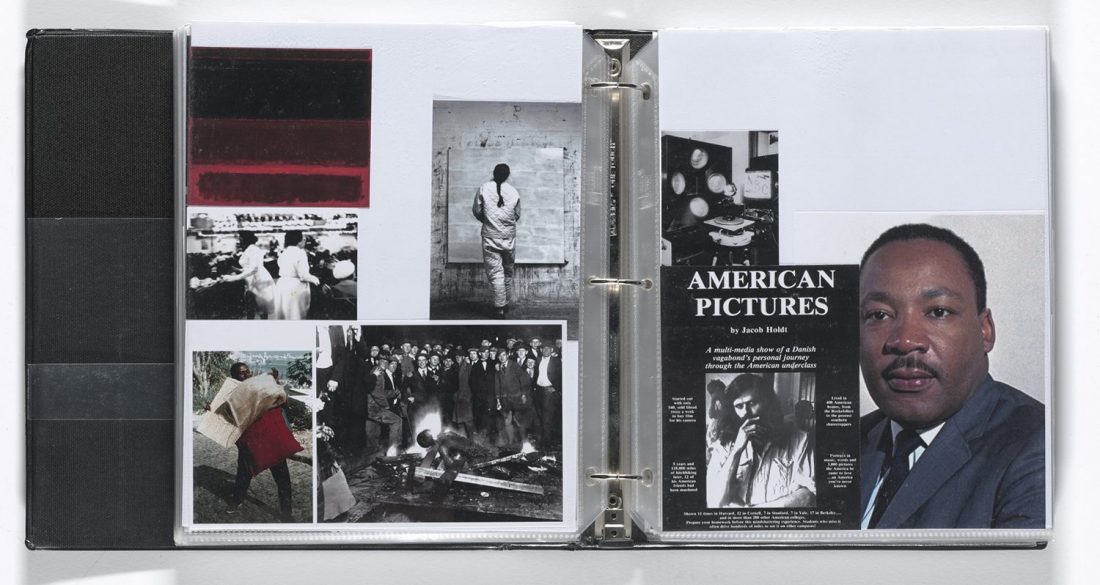

Detail of Arthur Jafa, 'Untitled Notebook', 1990–2007. Copyright Arthur Jafa

Courtesy the artist and Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels (full image below)

CONTENT GUIDANCE

Please note, this journal post contains images depicting violence and partial nudity, and contains graphic references to violence in the text.

Generating Space(s) refers to the knock-on effect resulting from the use of archives in praxis.

When we make space for the opening of archives, for engaging with them in new critical ways, for extrapolating their contents, and developing new means of displaying what they comprise, we are able to generate new indexical presents¹, new spaces for discussion, for both learning and unlearning.

Proximity, Affect, Effect

The Russian and Soviet filmmaker Lev Kuleshov, who was active from the mid-1910s until shortly before his death in 1970, is remembered as a key figure in the development of Soviet montage, furthermore, his articulation of the technique’s capacity to emotionally influence and persuade an audience. The phenomenon, known as the Kuleshov effect and demonstrated here by Alfred Hitchcock, is defined as follows: the viewer of a film will derive more meaning from the interaction between two consecutive clips of a film than from one of those shots in isolation.

What then of viewing consecutive images?

Referring to the artist John Akomfrah when in conversation with curator Hans Ulrich Obrist in 2016, Arthur Jafa recalled how Akomfrah referred to his practice as the taking of things and the placement of them in ‘some sort of affective proximity to one another.’ He continued, ‘That really hit me because I think for me, in a nutshell, that’s what it really comes down to.’ Jafa, who has enjoyed global recognition as a conceptual artist since the premiere of his 2016 film Love is the message, the message is death and his subsequent taking of the top prize at the 58th Venice Biennale for The White Album (2019), has long demonstrated the possibilities of affective proximity (the capacity for the proximity between pieces of art, in this instance, to affect the viewing experience of one another). Even beyond the projects that made his name as a cinematographer, like Daughters of the Dust, the 1991 film directed by his then-wife Julie Dash, Jafa would nurture archives of non-moving images. He understands the potential collected images have to affect one another, and in turn, affect us.

Between 1990 and 2007, Arthur Jafa arranged images torn and clipped from a plethora of sources into the clear plastic sleeves of three-ring binders. ‘What began as a mobile mood board evolved into a living archive, […] which, particularly alongside Love is the Message, demonstrates how Jafa has for decades constructed a ‘specific’ visual culture that grounds his indexical present in individuality and autonomy as markers of subjecthood. The combinations of images in his binders are personal and conceptual, intuitive and aesthetic, disturbing and revealing.’ writes curator Isabel Parkes in an essay for Burlington Contemporary.

On some pages, the correlation between the images populating Jafa’s three-ring binders needs not be spoken of, whereas on others, the assemblages seem incongruent (a blood-covered Sid Vicious; the Kaaba at Mecca; the cover of Hunter S. Thompson’s 1967 book Hell’s angels: The Strange and Terrible Saga of the Outlaw Motorcycle Gangs; Charles Manson; and lastly, a complicated leitmotif of Jafa’s: the deeply scarred back of the former enslaved man, Gordon).

We should read these visual leaps and unfamiliarities as a testament to the visceral discomfort of the lived Black experience, the inexplicable Black joy-suffering paradigm. In this way, it only makes sense for the image of the smouldering corpse of a lynched Black man gazed upon by a crowd of white men, many of whom eye the camera with malice to be placed within close, affective proximity to a portrait of Martin Luther King Jr. in which he looks rather absent-minded, perhaps even bemused.

Arthur Jafa, ‘Untitled Notebook’, 1990–2007. Copyright Arthur Jafa

Courtesy the artist and Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels

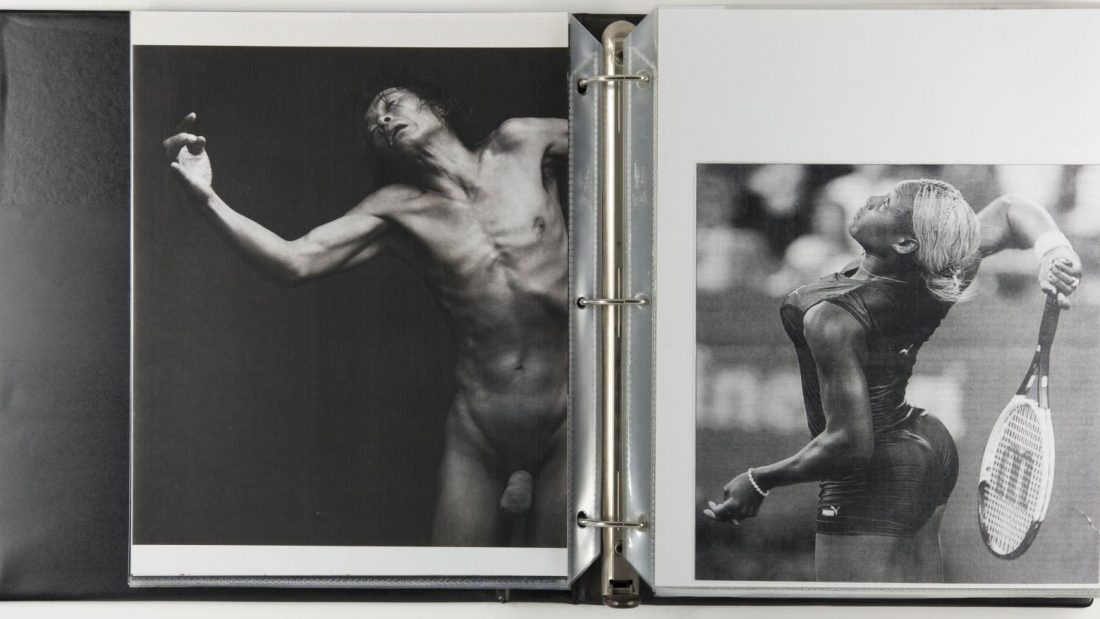

Arthur Jafa, ‘Untitled’, 1990–2007. Copyright Arthur Jafa

Courtesy the artist and Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels

Activate? Decolonise.

Calls to ‘decolonise’ ring loud through the digital discourse on contemporary art, yet it seems the definition of the word has adapted beyond its original meaning. Whereas a twentieth century understanding of the term would have been relegated to the description of the literal removal of colonial forces from occupied lands, today, it seems to refer to the untangling of the intangible, the undoing and unlearning of the cultural and social implications of global imperialism as they remain in allegedly ‘postcolonial’ societies.

Amidst the swathe of calls to action to decolonise minds, decolonise institutions, and decolonise academia in light of global Black Lives Matter action, how can we decolonise archives? Vast bodies of objects and materials through which we can access and attempt to understand the past ways of non-European cultural traditions, many of which were partially eradicated and demonised by the imperial forces which then looted the objects most significant to them.

So, what does the proactive use of an archive look like? It must be the extrapolation and critical curation of its contents. It must be the restitution of ideas. (It is important to note the ways archives differ. Within the context of this section, I will focus on written archives, though I must note how archives of objects i.e. artefacts, archives of sounds, and archives of moving images can be discussed under vastly different terms, which I will explore in the second part of this research project.)

Archives are overwhelming. Radical pedagogy comes about when information formerly relegated to the elitist confines of academic spaces can be redistributed to the public via accessible mediums. Artist Tiffany Sia, who founded and continues to operate Speculative Place, an experimental, independent project space supporting artists and cultural workers working with film, words, and art in Hong Kong. As a part of Home Cooking, a global artists’ collective and ‘digest of new worlds, activities, poetry, movement and live events’, Sia contributes Hell is a Timeline, a weekly performance series in which the artist appears via livestream, reading aloud a series of selected texts (‘[Sia] uses reading aloud as a tool of pedagogy and care.’) The series is archived on Vimeo, and transcripts of past performances can be accessed via the Home Cooking Google Doc.

![<p>Tiffany Sia, <em>Hell is a Timeline [On Citizenship in Entropy]</em> (still)<em>,</em> 2020</p>](https://www.southlondongallery.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/4-—-Still-from-Hell-is-a-Timeline-On-Citizenship-in-Entropy-2020-Tiffany-Sia-video-31-minutes--1100x872.jpg)

Tiffany Sia, Hell is a Timeline [On Citizenship in Entropy] (still), 2020

For Los Angeles-based artist-run publishing and educational platform Cassandra Press, the restitution of information finds form in the production of ‘lo-fi printed matter, classrooms, projects, artist books, and exhibitions,’ their intention being to ‘spread ideas, distribute new language,’ and ‘propagate dialogue centring ethics, aesthetics, femme driven activism, and black scholarship.’ The press, founded by critical theorist and artist Kandis Williams, produces a number of readers, booklets available for purchase (as either a physical object or a PDF file) comprising selected critical texts ruminating on a specific theme. Cite critics Christopher Lebron and Marcy C. Beltrán in the READER ON Black and the Silver Screen; break down the thoughts and theories W.E.B. Dubois, turn the page, then read Jalal Toufic in the READER ON the Double Consciousness Then and Now.

Reader on Essentialism, Essence, and Disorder, 2020. Image credit: CASSANDRA PRESS, Kandis Williams

Cassandra Press’s readers function as manuals, too. The compilation of magazine articles with academic papers and reviews and personal essays demystifies the practice of critical thought, allowing for a local contextualisation of esoteric concepts and academic theory. The inclusion of contemporary texts encourages a viewing of time beyond the linear passage, as regular referral to past, present, and even speculation into the future is required to wholly appreciate the contents of each booklet.

‘I am talking about societies drained of their essence, cultures trampled underfoot, institutions undermined, lands confiscated, religions smashed, magnificent artistic creations destroyed, extraordinary possibilities wiped out.’

Aimé Césaire, ‘Discourse on Colonialism’ (1950)

In order to reconcile cultural evisceration on this scale, archival praxis should look both to the past, and to the future. This process should entertain combinations of texts and objects that speak to the ‘extraordinary possibilities’ Césaire writes so urgently about; the process should be speculative.

Generating Space(s) Part II will extend the register in which we may approach contemporary notions of decolonisation through archival praxis.

ABOUT

Olamiju Fajemisin (b.1998) is a critic, editor and curator based in London where she studies at The Courtauld Institute of Art. She has written for various publications and institutions, including Contemporary&, frieze, Kunsthall Bergen, and the Salzburg International Summer Academy of Fine Arts. She is the Deputy Editor at biannual Zürich-based contemporary art publication, PROVENCE.

BLACK LENS is an alliance of young Black writers, art historians and curators assembling around Black research, scholarship and cultural production.

Convergence is an ongoing series of critical conversations, screenings and written commissions, facilitated by the SLG and curated and hosted by invited guests.

1. ‘[Adrian] Piper describes the “indexical present” as a directed attentional focus on the immediate here and now; basically mindfulness that is pointed to a particular moment, a moment of contact.’ Julia Steinmetz, ‘The Power of Now: Adrian Piper’s Indexical Present’, May 7 2009, art21 magazine https://magazine.art21.org/2009/05/07/the-power-of-now-adrian-pipers-indexical-present/#.X2eKb5MzZE8