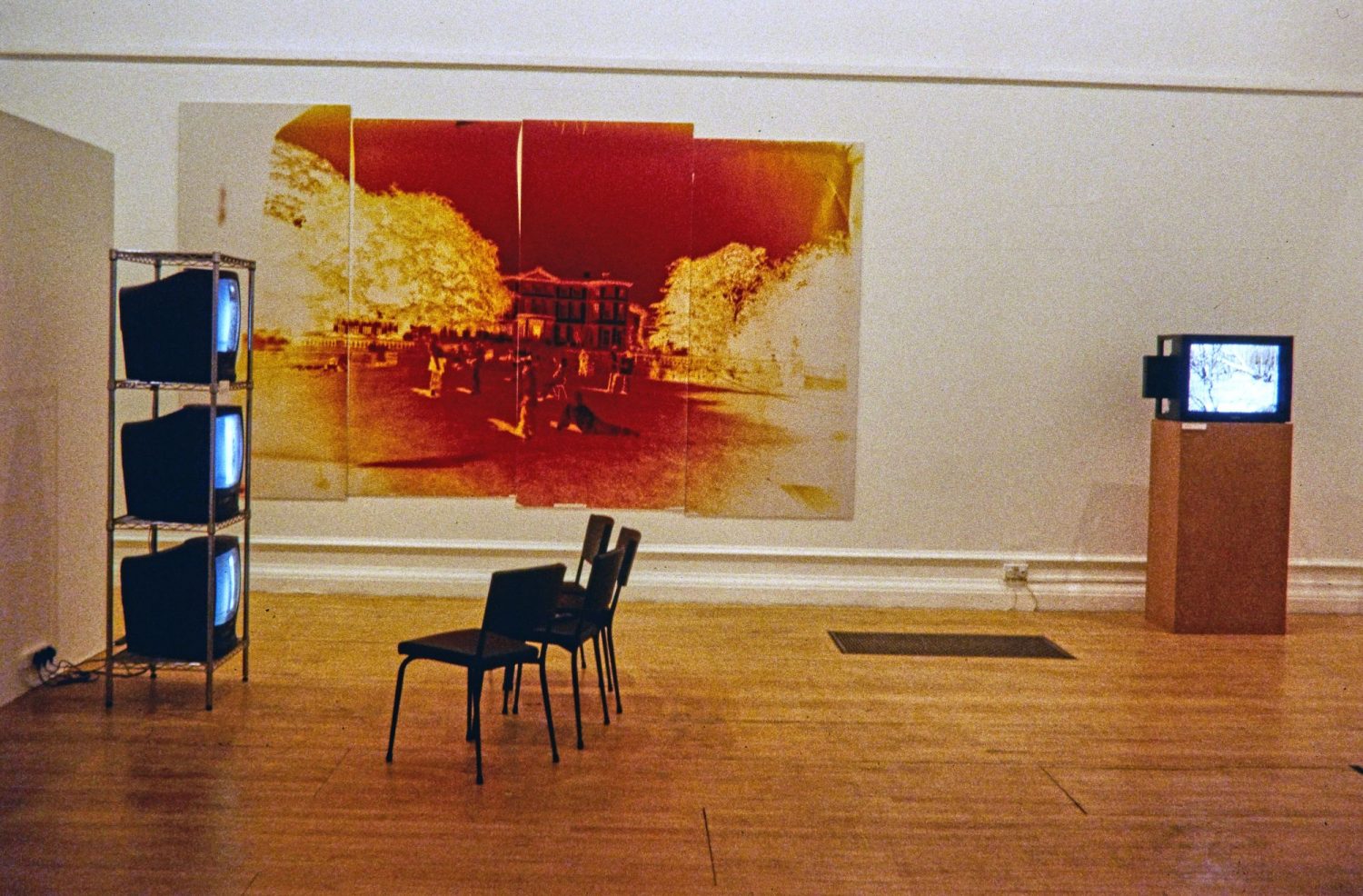

Installation view of New Contemporaries 99 at the South London Gallery

The South London Gallery (SLG) is currently hosting New Contemporaries, almost twenty years after this annual touring exhibition was last shown at the gallery.

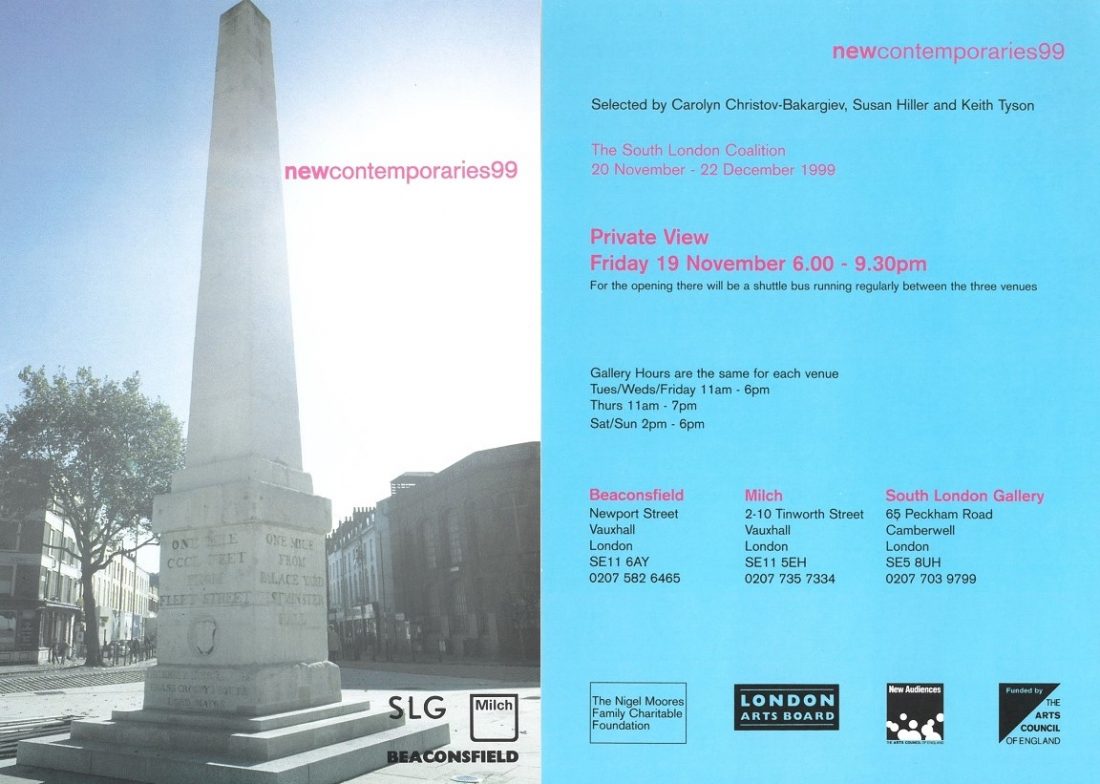

New Contemporaries has been providing a platform for artists at an early stage in their careers since 1949 (when it was called Young Contemporaries). This year’s exhibition marks the second time the SLG has participated in the show, the first being in 1999. Then, as now, the works were shown first as part of the Liverpool Biennial before moving to the capital. The Biennial’s inaugural festival took place in 1999; it had been established the previous year by James Moores, who had been a supporter of New Contemporaries since 1996. Back in 1999, however, the SLG’s only exhibiting space was the Main Gallery, which was not large enough to accommodate all the artworks. The solution was slightly unusual; a collaboration between the SLG, Beaconsfield and Milch saw the exhibition being spread across all three South London venues.

Invitation card to the private view (front and back)

Following an open call, to which over 1,000 people submitted entries, works by 33 artists were selected by a panel made up of British artists Susan Hiller and Keith Tyson and Italian critic and curator Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev. Of the thirteen artists exhibiting at the SLG, nine presented some form of video art. The subjects of the films ranged from close observations of home and away football fans at Crystal Palace stadium (Julie Henry, Going Down) to footage which celebrated differences between cultures whilst critiquing western values (David Harding, Voices from Two Hemispheres). Amongst the other video artists exhibiting was Nicole Wermers, who was nominated for the Turner Prize in 2015. Her work Palisades explored the manipulation and perception of architectural space by turning her camera upside-down on her subject. Other pieces included Peter Richards’ unique pinhole photographs (Another Day, Another History of Performance Art) and Kentaro Chiba’s meticulously detailed ink drawings (Life Scroll).

Kenny Macleod’s video Robbie Fraser drew particular attention and was commented upon by both Jonathan Jones in the Guardian and Sarah Kent in Time Out.

A young man’s head appears on video. Surrounded by white, so that nothing distracts attention from his words, he tells us about himself. “Hello, my name is Robbie Fraser. In November 1996, I split up with my last girlfriend…”, “Hello, my name is Robbie Fraser. When I moved into my new flat, the garden was in a real mess…” But as the story unfolds, discrepancies begin to appear. “Last year, my wife and I had our first child…”, “In November 1996, I split up with my last boyfriend…” Gradually, it dawns on you that the character is fictitious and the episodes he recounts are off-the-peg biographies – potential experiences awaiting adoption. Life begins to seem like a shopping trip, a search for outfits that fit. If Fate is a designer label, where does that leave art? Intelligently questioning the idea of subjectivity, of course.