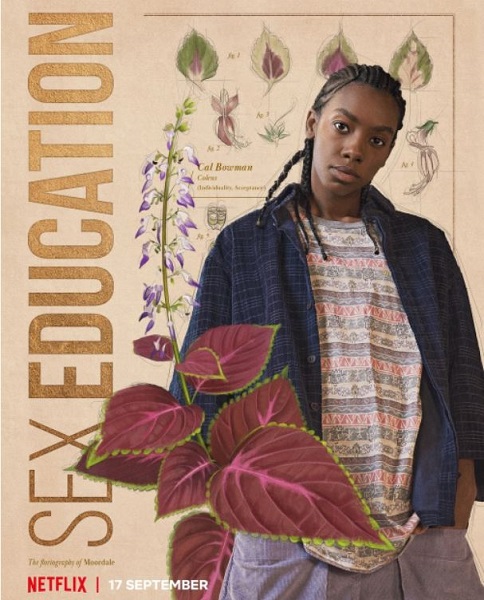

Cal Bowman from Netflix's Sex Education

THIS ARTICLE BY MULTIDISCIPLINARY ARTIST ABENA ESSAH IS PART OF THE SPREAD THE WORD SERIES, COMMISSIONED FOR THE SLG’S CONVERGENCE PROGRAMME.

How do we grapple with and healthily keep the parts of ourselves that we want to preserve and grow, in a world that gatekeeps the nuances of queer experiences – especially for black queer individuals?

Netflix original series ‘Sex Education’ follows the lives of teenagers at Moordale Secondary School. Initially, the show’s premise is centred around Otis, played by Asa Butterfield, who starts an unofficial sex clinic in school with Maeve Wiley, played by Emma Mackey, to help solve the issues and queries of their peers. However, as the seasons progress the premise of Sex Education goes far beyond the sex clinic and delves deeper into the individual lives of different students, exploring their nuanced identities and relationships.

In Season 3, the most recent season of ‘Sex Education’, we get to meet Cal Bowman, played by Dua Saleh. Cal is a black, dark-skinned, non-binary student, who graces our screens as the new kid at Moordale Secondary School with a skateboard and undeniable presence. I will never forget the moment that Cal officially introduced themselves on screen, immediately correcting Jackson Marchetti, played by Kedar Williams-Stirling, as he introduced and misgendered them as ‘she’, to which Cal states, “My pronouns are they/them, but no worries”. My goodness, how I needed Cal as I grew uncomfortably into my own teenage skin, before painfully peeling back a girlhood I was told not to reconsider – until I finally did in my early twenties, when I came out as non-binary.

*Disclaimer – Season 3 Spoilers below*

In season 3, Eric Effiong – played by Ncuti Gatwa (Otis’ bestfriend and one of my favourite, fabulous and hilarious black humans in Sex Education), is officially in a relationship with Adam Groff, played by Connor Swindells. In order to set the scene, it is important to note that Adam is white, pansexual, and not fully out of the closet. Also, he used to bully Eric – most likely due to his own internalised homophobia. Why do I say this? Because Eric desires loud freedom, to love everything about himself from his heritage to his queer identity – a freedom that is arguably not guaranteed with Adam.

I want to draw close attention to episode 6 of this season, where Eric returns to his motherland, Nigeria, to attend a family wedding and reconnect with extended kin. Here, he meets Oba, the wedding photographer, who plunges Eric into deep euphoric waters when he cryptically reveals his own queer identity, flirting before leading a curious yet suspicious Eric into an underground queer scene in Lagos. Eric is overcome upon arrival, his face a bolt of light as he looks around. “How do you feel?” Oba asks, to which Eric replies “I feel like I’ve come home”. Never have I seen a queer homecoming for a child of the Nigerian diaspora on British television. The scene at the queer night in Lagos was filmed with such intentional and emotion-inducing colour – purple, red, blue hues, drawing parallels for me with season 1 of HBO’s Euphoria. Neon and intense, Eric’s homecoming portrayed black queerness as a matter of fact, rather than a gimmick, which I appreciated – with all thanks to Temi Wilkey, the seasoned writer of Nigerian heritage who wrote the episode.

This season, Cal and Jackson Marchetti also intertangle and tentatively fall for each other; yet their relationship is fraught with misunderstanding. Jackson uses gendered compliments with Cal, doesn’t check in with Cal about where they might experience dysphoria during the intimate moments they share, and isn’t comfortable with notion of being in a queer relationship. In episode 8, when Cal makes the decision that Jackson and them should be friends instead of lovers, what Cal says to Jackson will stick in my mind for a while: “I’m not a girl, and I’m worried you still see me as one”. While Jackson states that he is willing to learn, to be educated, Cal is decided: “I’m still figuring out so much shit about myself, I can’t carry you too.” In this way, Cal insists on being loved and seen in all of their multitudes.

Both Eric and Cal’s stories lead me to ask the question: what does it mean to come home in your entirety with regard to your heritage, or with regard to your body as a black queer individual? Queerness, I believe, requires you to kill the version of yourself that you were given at birth in order to unearth a new understanding of yourself – this is often as separate from toxic societal offerings as humanly possible. After this rebirth, what does it mean to navigate love in a world that often fails to see you for your entirety? What does it mean to then intermingle with the very thing that you were running from in the first place, in order to be a ‘functioning’ member of society?

Cal’s experiences, from awkward relationships to being jeered at in the girls’ changing rooms for wearing their chest binder, made me mourn the rich queer and gender diversity that existed pre-colonially. The truth is that the ridicule that Cal faces, and that many trans and non-binary people face for being who they, are stems from colonial erasure of black and indigenous cultures. This erasure is active to this day, through transphobic legislation and the decision to not teach about the breadth of gender diversity, indigenous cultures and identities in mainstream education. This keeps trans and non binary identities appearing as “new” or deviant in society, which is an attempt to replace an innate capacity for fluidity with a legacy of transphobia. Alok Vaid-Menon, a non-binary cultural leader who performs under the moniker ALOK, often talks about how European colonists targeted trans and gender variant people from black, indigenous and people of colour communities: “Because they knew our power, that’s the reason there is such animus against [us]… they try to repress us because they did that to themselves first”. [1]

As an artist, I often turn to the archive in my practice to hold space for the truth, to remind myself that I come from a people who didn’t see blackness, queerness and nuance as a question, but as a fact. Shanna Collins, in an online article for Medium, explores ‘the splendour of gender-nonconformity across Africa’ before the infilitration of ‘rigid European binaries’. [2] For instance, the Dagaaba Tribe in my homeland, Ghana, assigned gender based on the energy an individual would radiate. And in ‘Boy-Wives and Female-Husbands: Studies in African Homosexualities’, [3] we also learn that the Fanti tribe in Ghana believed that regardless of gender, those “with heavy souls would desire women… and those with light souls would desire men”. Thus, as queer black people, just by existing we are pointing back to what was taken, yet is resilient in us to this day. This is why stories like Cal’s and Eric’s are essential.

Though I didn’t always agree with Eric’s choices in Season 3 of Sex Education (Eric’s irritation when Adam had cold feet about intimacy during the picnic or the way Eric went about breaking up with Adam), I do deeply understand Eric’s deep desire in episode 6 to kiss Oba so tenderly. It was more than just a kiss – it was vicious hunger to come home, in all of his entirety. I couldn’t help but draw up heaps of emotion watching Eric, as a child of the Ghanaian diaspora myself, especially with the context of the homophobic laws brewing in my homeland right now and my own deep and complex desire to be seen, to come home.

Cal and Eric represent so many facets: centring gender euphoria in everything, and choosing your heritage and queerness when it has been drilled into you that it is not possible. But it is.

Queer nuance is essential. Black queer nuance is a breath of fresh air.

[1] The Man Enough Podcast – ALOK: The Urgent Need for Compassion (11:35 – 12:18 minutes)| The Man Enough Podcast

[2] Collins, S. (2017). The Splendor of Gender Non-Conformity In Africa [online], Medium, October. Available from Medium [Accessed on 10 February 2022]

[3] Murray, S. O., and Roscoe, W., eds. (1998) Boy-Wives and Female-Husbands: Studies in African Homosexualities, New York: Palgrave for St Martins Griffin

Abena Essah, Image © Sylvia Suli

BIOGRAPHIES

Abena Essah is a multidisciplinary artist based in London, a poet, musician, actor and creative of many hats. Their poetry often explores personal identity focusing on intersections of their queer identity, music, Ghanaian heritage and untold black history. Abena Essah has been published by Spread the Word with Ink Sweat and Tears and performed their music and poetry at the Southbank Centre with Outspoken Live, the Brainchild Festival, and featured on the Channel 4 documentary Hair Power: Me and My Afro. They are a finalist of BBC Words First and a Some-Antics Slam Champion. They are an alumnus of the Obsidian Foundation and The Writing Room and currently a Barbican Young Poet and Roundhouse Resident Artist. Abena Essah is working on their debut EP and debut theatre show.

Spread the Word is London’s writer development agency, a charity and a National Portfolio client of Arts Council England. It is funded to help London’s writers make their mark on the page, the screen and in the world and build strategic partnerships to foster a literature ecology which reflects the cultural diversity of contemporary Britain. Spread the Word has a national and international reputation for initiating change-making research and developing programmes for writers that have equity and social justice at their heart.

In 2020 it launched Rethinking ‘Diversity’ in Publishing by Dr Anamik Saha and Dr Sandra van Lente, Goldsmiths, University of London, in partnership with The Bookseller and Words of Colour. Spread the Word’s programmes include: the Young People’s Laureate for London, the London Writers Awards and the national Life Writing Prize.

Convergence is an ongoing series of critical conversations, screenings and written commissions, facilitated by the SLG and curated and hosted by invited guests.